We all deal and react to trauma differently. I’ve experienced this while working with children and young people in the child protection system and their natural and foster families, working with children with challenging behaviours, veterans, people with acquired injuries (permanent disabilities), victims of crime and their perpetrators, adult survivors of child sexual abuse, people with a disability on forensic orders, violence against women, people who have been bullied within a range of areas such as in the workplace, and schools, and everyone in between.

Trauma involves exposure to a situation for example, that threatens or where there is actual death, serious injury, sexual violence and abuse, car accidents, physical assault, home invasion, violence, environmental events (e.g. cyclone, fire or floods), or the loss of a job. Trauma can also be an event that is seen as being a stressful experience that the person experiences as highly traumatic. This can include when a person has witnessed such events happening to another person, learning that a loved one has been involved in one of these events, or vicariously experienced through others talking about the event.

When it comes to Trauma, Francine Shapiro (2001) talks about Capital ‘T’ for Trauma which covers the type of situations that were discussed above, and little ‘t’ for Trauma such as incidents that occur in our lives that we find difficult to deal with but are still deemed as being a stressful event and highly traumatic for the individual. For example, a little ‘t’ experience could occur when a child has to stand up in their year 4 class and give a presentation. During the presentation, they hear one of their classmates chuckle at them, and say something under their breath. When this type of incident occurs, some children will just shrug this event off and move on with their day, and some may be initially effected and take a couple of days to get passed this situation. This group of children may not have liked the situation, and may have felt some emotions around the event, but ultimately, they were able to move on from this event without too many issues. However, some children would not have been able to move on from this event. Instead, they internalise this event. The feelings that arise include feeling incompetent, useless, embarrassed, ashamed, as well as imagining that people are calling them an idiot or other such names. For these children, the traumatic feelings and emotions around this incident grows. Due to this incident, the child may then avoid having to get up in public to speak, they may avoid going to social events, or they may sit in a different place for lunch away from the other children, all because they fear being humiliated again. They may avoid engaging in anything that will put them in the eye of others for personal judgement and being embarrassed or degraded in some way. Children who are not able to deal with such situations may act in differing ways. For example, one child may become quiet, depressed, and disengaged, where another child with the same experience may act out, and teachers and parents may see an increase activity in defiant behaviour … after all, they are just trying to get out of the way of ‘perhaps being judged and humiliated again’. Their world becomes smaller and smaller.

So, when you look at this view, many people will experience some type of trauma in their life time. The good news is that memories of trauma will often resolve by themselves, over time … but there are times when they don’t. Sometimes, traumatic events cause such emotional distress for people, and reactions from the trauma continue to plague their lives. When this occurs, the person may not be able to stop thinking about the event, intrusions may occur, and behaviours may start to transpire that assists the person in avoiding anything to do with the traumatic event or avoid the possibility of the event occurring again, which can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health 2013).

I often hear people talk and say they ‘just need to get over it’ like it’s their fault that this has occurred. But this is not true and once the blame and shame of having PTSD is put aside, with the help of a trained therapist, people can live in a way where their traumatic experience doesn’t hijack their lives.

When trauma or a traumatic event has been resolved it loses its vividness and fades into being “just another memory”. It doesn’t have the emotional hold over the person anymore. People can talk about the incident without it bringing up strong emotions or vivid memories or visions.

PTSD leaves a person experiencing:

- flashbacks

- distressing dreams of the event

- high levels of fear

- tensed muscles

- knotted stomach

- terror

- numbness

- anxiety

- depression

- insomnia

- avoiding or acting out and attempting to avoid thoughts and feelings associated with the trauma

- avoiding activities, places or people that will trigger the trauma

- emotional distancing and detachment from others

- a lack of positive feelings

- a pessimistic future

- difficulty in remembering details of some part of the event and vivid memories of other parts of the event

- problems concentrating

- being easily startled, and feel they are on guard most of the time

- increasingly getting angry or irritable, yelling at people, getting into fights, destroying objects, and then get angry at themselves for feeling and acting this way

People suffering from PTSD may feel unsafe, feel that they are helpless, and feel that they are unable to trust others, with many other emotions being linked to their traumatic event. These feelings and emotions are a normal part of PTSD.For example, let’s look at an event for a moment and try to explain how the person experiences this trauma.A woman experiences a traumatic event such as a motor vehicle accident. Just before the accident, she is driving through an intersection that she has driven through thousands of times before. She is not speeding, and she has a green light. All of a sudden, out of the corner of her eye, she sees a car on her right coming towards her car. She has no time to stop, or to go faster to miss the car. The cars impact. A memory of that traumatic event continues to haunt her more than 1 month after the event (i.e., driving through a green light with the car coming towards her, and she continues to experience the sight of the other vehicle coming though the windscreen a fraction before impact. She sees this through flashbacks many times during the day, she sees this in her sleep and wakes with a startle). Her emotions and body remember the feelings and sensations that went along with the event (i.e., a sense of fear, tensed muscles, knotted stomach) and she places a meaning with the traumatic event for example, “I am not safe”. From a very basic low level biological view, let’s take a quick look at how traumatic events cause changes in the brain structure, as it is a bit easier to understand why the woman in the car accident is experiencing these reactions.

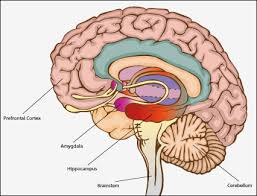

Let’s take a look first at the Amygdala. Processing, integration and interpretation of emotional information occurs here. This area increases your arousal and responses associated with fear, is the site where anxiety is perceived, and this area applies feeling and emotional charge to a memory (Davis, 1992a, cited in Perry, 2008). The fear induced by trauma makes it seek out threats everywhere, as when you have been in trauma the Amygdala is hypersensitive and overreacts to normal stimuli.

The Hippocampus involves memory and encoding new information. It is responsible for the formation, organisation, storage and retrieval of cognitive and emotional memories, and is very sensitive to the activation of stress (Phillips and LeDoux, 1992a, cited in Perry, 2008). Trauma alters the hippocampus ability “to store certain types of cognitive information (e.g., verbal) but does not affect the storage of other types (e.g., nonverbal)” (Perry, 2008, p.13). Therefore, trauma stops the process that allows context to be transformed into memories, so the memories remain activated. For example, bringing the accident above into view, the person drove through the green light and had the accident, but she is anxious every time she goes through a green light, even though she has gone through green lights thousands of times without having an accident. The Amygdala over-rides the hippocampus and any kind of context doesn’t make sense. Memories are fragmented as they have been stopped from being properly integrated.

Then, we take a look at the prefrontal cortex. This part of the brain engages in integration, planning, regulating behaviour, deciding on actions, taking information from the body’s senses etc. Perry (2008) states with PTSD that external stimuli are “mislabelled as being a threat…thereby inducing a fear response…in situations where no true threat exists…and the general disinhibition characteristic of this syndrome suggests loss of the capacity to interpret incoming threat-related cues from lower brain areas”(p. 14). So we can see that the hypersensitive Amygdala inhibits the pre-frontal cortex, including the functions that this area of the brain is to perform, hence the behaviour people see from others who are experiencing PTSD.

People with PTSD also have a higher probability to suffer from depression, anxiety or phobias.

There are many areas of the brain that actively play a part in Trauma, but it is easy to see that people can’t just ‘get over’ it. The brain of a person who has PTSD is wounded and needs care just as any other part of the body is cared for, when wounded.

If you know someone who can benefit from some help, please encourage them to see their doctor. When it comes time to find a therapist, they need to feel comfortable and trust them. They will be given information around the type and length of treatment they will receive, and they can talk with their therapist and decide if they feel that is right for them. For example, around Trauma I personally use EMDR – Eye Movement Desensitisation Process, and ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy – see website for details around these therapies www.mindset.synergy.com.au), however other evidenced based therapeutic interventions can be used by your therapist. Take the step toward the future, and I wish you all the best.

References:

Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health http://acpmh.unimelb.edu.au/resources/index.html

Perry, B.D., (2008). Child maltreatment: A Neurodevelopmental perspective on the role of trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. Retrieved September 17, 2014, from https://childtrauma.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Perry_Psychopathology_Chapter_08.pdf

Contact us on

Contact us on

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Linkedin

Linkedin